Continued from part 1 of this essay.

Essay by Majken Hirche, part 2 of 2.

Conquering the World

Since George Washington there has been a belief in the U.S. that the ‘impression of others’ matter.[1] This is quite spectacular for a nation, and can only be understood in terms of an exceptionalist promise to the future: that the “empire of liberty”, which itself had struggled so much for independence and democracy, now wants to be a role model for the rest of the world. According to literary critic Sacvan Bercovitch, a great deal of New England Puritanism was part of this ideological mix, reframing and transforming narratives from the Old Testament into a new historical mission of the ‘American Jeremiad’[2] who “has the power to begin the world all over again,”[3] and build a “new Jerusalem in the wilderness.”[4]

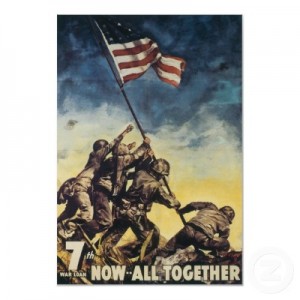

In order to make such a self-definition work, the non-Americans – the ‘others’ – needed to be less civilized. Or they needed to be evil. Thus, “Manichean categories of New World versus Old or free world versus slave”[5] were the most easy concepts to deploy in public, and luckily for the U.S. there were plenty of candidates around the world which in fact did fit this description – the two most notorious being Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. Parallel to the biggest battles in the 20th century, the Second World War and the Cold War against Communism, America emerged as a Superpower, not only in terms of its military and economic might, but also in its irresistible confidence of moral and cultural superiority. Not only did USA build better missiles and invent supermarkets, it also created Hollywood and superheroes such as Superman and Captain America, who became immensely popular icons of the American spirit. They did – and still do – all the necessary cleaning, just like a very cool broom, and they have even been exported successfully to the whole world.

In order to make such a self-definition work, the non-Americans – the ‘others’ – needed to be less civilized. Or they needed to be evil. Thus, “Manichean categories of New World versus Old or free world versus slave”[5] were the most easy concepts to deploy in public, and luckily for the U.S. there were plenty of candidates around the world which in fact did fit this description – the two most notorious being Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. Parallel to the biggest battles in the 20th century, the Second World War and the Cold War against Communism, America emerged as a Superpower, not only in terms of its military and economic might, but also in its irresistible confidence of moral and cultural superiority. Not only did USA build better missiles and invent supermarkets, it also created Hollywood and superheroes such as Superman and Captain America, who became immensely popular icons of the American spirit. They did – and still do – all the necessary cleaning, just like a very cool broom, and they have even been exported successfully to the whole world.

The reference to the Christian tradition and the idea of an American Jeremiad is important in yet another respect: namely in its missionizing techniques by which to convert infidels. Just as it was the case with Paul the Apostle, the belief in an exceptional idea slowly became second to the mission to communicate the idea and make people believe in it. From solely being defenders of an exceptional idea, certain members of the American intelligentsia became crusaders of Americanism endorsing ‘noble lies’ as formulated in Plato’s Republic, by which “myths used by political leaders” should be employed in order to “maintain a cohesive society.”[6] With the publication of books such as ‘The City and Man’ (1964) by Leo Strauss and especially the early ‘Public Opinion’ (1922) by Walter Lippmann, a journalist and political adviser to President Woodrow Wilson, the mission of the apostles and crusaders had gotten a philosophical license to use “stereotypes”[7], myths and noble lies in order to “manufacture consent”[8] – a term later used by Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky in their highly critical book, Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media (1988), on modern manipulation of the public by the mass media.

After World War II the idea of the U.S. having inherited a global responsibility to promote freedom was more or less endorsed by the mainstream press.[9] According to vice president Henry A. Wallace the United States should promote “freedom not merely by example or occasional international intervention but via an unending involvement in the affairs of other nations.”[10] This double edged political program of unilateral military interventions had a few successful moments, especially with the airlift into West Berlin in 1948, the Invasion of Grenada (1983) and the intervention in Bosnia and Kosovo in 1995 (via NATO). But most of them were more dubious, and did not necessarily have the promotion of democracy in mind. On the contrary, in 1953 the democratically elected Prime Minister of Iran, Mohammad Mosaddegh, was overthrown with the help of CIA and MI6. One year later the same happened for President Árbenz Guzmán in Guatemala, and in 1961 the U.S. backed the assassination of the South Vietnamese president Ngo Dinh Diem. During the Vietnam War the democratically elected President of Chile, Salvador Allende, was overthrown in 1973. The U.S. also backed the military rulers of El Salvador, and the contras of Nicaragua, beginning in 1981. In 1982 U.S. backed Saddam Hussein in order to fight Iran, and during the 1980’s they supported the Mujaheddin and Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan in order to fight the Soviets.[11]

Many of these military interventions were seen by the international community as imperialistic crimes, not as exceptional enablers of freedom and democracy. Only by name (“Operation Just Cause”, “Operation Fortune”, “Operation Success” etc.) and by the ‘manufacturing of consent’ they kept a hint of the American spirit – e.g. Captain America’s defence of liberty and democracy from tyranny. In reality, they had everything to do with the communist containment policy of the Truman Doctrine,[12] with controlling ‘America’s backyard’ and, if opportune, with keeping (tyrannical) friends in power.

All these double standards became truly exposed after the unfortunate September 11 attacks in 2001, when a confused and furious American leadership invaded Iraq (“Operation Iraqi Freedom”) on false pretences. To many people inside and outside of the U.S., the 50 year old image of USA as a superhero changed in 2003 from being Captain America to becoming The Incredible Hulk: uncontrollable rage befell the New World, and anybody who just once had said hello to a ‘terrorist’ would by definition be suspected of being a terrorist himself. Even more disturbingly, some of the Civil Rights achievements during the last 200 years started to be annulled. The Patriot Act of 2001 gave the police powers to “arrest suspects, snoop, secretly enter people’s homes without notice and freeze bank assets […] indefinitely, in secret and without legal remedy.”[13] Bush approved the use of torture in secret prisons worldwide, and the defence and intelligence agencies were allowed to gather information on any person at any time.[14] The Obama administration proved different, but only in style. Instead of abiding to Habeas Corpus as a central principle in the Rule of Law, Obama choose to detain a solider accused for leaking classified material to wikileaks (Bradley Manning) indefinitely, and break him psychologically as deterrence for others. And instead of throwing ‘terrorists’ into Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib prisons, as Bush did, Obama prefers to kill them. The Obama administration even keeps a secret and updated “kill list”[15] of which some are American citizens, and the only justification for this conduct is repetition of the words “just trust me”.[16]

All these double standards became truly exposed after the unfortunate September 11 attacks in 2001, when a confused and furious American leadership invaded Iraq (“Operation Iraqi Freedom”) on false pretences. To many people inside and outside of the U.S., the 50 year old image of USA as a superhero changed in 2003 from being Captain America to becoming The Incredible Hulk: uncontrollable rage befell the New World, and anybody who just once had said hello to a ‘terrorist’ would by definition be suspected of being a terrorist himself. Even more disturbingly, some of the Civil Rights achievements during the last 200 years started to be annulled. The Patriot Act of 2001 gave the police powers to “arrest suspects, snoop, secretly enter people’s homes without notice and freeze bank assets […] indefinitely, in secret and without legal remedy.”[13] Bush approved the use of torture in secret prisons worldwide, and the defence and intelligence agencies were allowed to gather information on any person at any time.[14] The Obama administration proved different, but only in style. Instead of abiding to Habeas Corpus as a central principle in the Rule of Law, Obama choose to detain a solider accused for leaking classified material to wikileaks (Bradley Manning) indefinitely, and break him psychologically as deterrence for others. And instead of throwing ‘terrorists’ into Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib prisons, as Bush did, Obama prefers to kill them. The Obama administration even keeps a secret and updated “kill list”[15] of which some are American citizens, and the only justification for this conduct is repetition of the words “just trust me”.[16]

Many critics ask today: where is the judicial review; where are the checks and balances; where is the American spirit, and what has become of the idea of ‘American exceptionalism’? One line of thought for finding an answer to these conundrums is that the introduction of manufactured lies and manipulations by the neoconservative movement in the 1920s and 1930s have become perceived as reality by the very same people,[17] and that they, unfortunately, came into power during the Reagan administration and later in the Bush administrations. This group of people had become so blinded by their Manichean world view of good and evil that they were convinced that the Soviet Union had been defeated by their arming of the Mujaheddin in Afghanistan, and not because the centrally planned Soviet Union had become an economic paper tiger deemed to collapse by itself.[18]

The beacon of liberty, freedom and democracy, exemplified by a suspended Columbia had slowly but surely evolved into missionizing, forced guidance, manufacturing of opinions and lying to oneself and to the people. The Obama administration might not be accused of deliberate deception, but according to some commentators[19] [20] it has accepted and deployed the “confidence multiplier”, a concept developed by George Akerlof and Robert Shiller,[21] in order to repair public trust in the government. A ‘confidence multiplier’ is the same as saying “just trust me”. It can be an important tool for calming the markets, giving people “hope”, and ensuring stability in foreign relation, but it can equally well be a convenient excuse for lying and deceiving.

From dust to dust

Much can be said about the differences between words and deeds. What is important is that the distance between them does not get too big, and when it does, realignment through a crisis or maybe even a Civil War will lead to the awareness that you have to learn from the mistakes and hopefully grow stronger. American exceptionalism, as exemplified by a hovering Columbia in Gast’s picture, has throughout this thesis been described as having all the qualities of a sweeping broom. This might (rightfully) be seen as a too simplistic analogy, but the hope was that it also could illustrate something important, namely the idea of exceptionalism as a dynamical process, where, borrowing from an expression by Lewis Carroll, it takes all the sweeping you can do, just to keep the same level of cleanness. When the real sweeping is replaced by forlorn handwaving and blatant lies, the basic premise for the United States of America as a ‘beacon of light’ disappears. Because of this, many commentators believe that America’s supremacy has suffered a dramatic decline in influence during the last 20 years. According to a prominent defender of exceptionalism, Joseph Loconte, some critics even have started to despise this diminished light as the quintessence of darkness when they “express their gloomy outlook: ‘The only city on a hill we resemble today is Mordor!’”[22]

In spite of all these grievances the United States of America has had an unprecedented effect on the liberation of the human imagination. It has inspired millions if not billions of people who have been raised by the preconception of the Old World, saying that the masses – the people – cannot govern themselves. This, above all, has been proven wrong by the American way. It IS possible to create your own life, to search for happiness and to decide for yourself, what is best for you. No other country had done that before. And bad for them, because the social, economical and political benefits that spring from an emancipated and self-determining population are still underestimated by the misanthropic rulers of the Old World. Therefore, for a foreseeable future, the United States will most likely continue to be an economic, military and cultural superpower, and the only thing that eventually will bring the U.S. down is a deterioration from within: getting devoured by the contradictions between ideas and actions, getting hijacked by old misanthropes, lost in chauvinist grime and complacency about the challenges ahead – like a broom that does not work anymore.

Bibliography

Aikin, R. C. (2000). Paintings of Manifest Destiny: Mapping the Nation. American Art, 14(3): 78-89.

Akerlof, G. A. & Shiller, R. J. (2009). Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Economy. Princeton University Press, New Jersey.

Becker, J. & Shane, S. (2012). Secret ‘Kill List’ Tests Obama’s Principles. The New York Times, online: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/29/world/obamas-leadership-in-war-on-al-qaeda.html?_r=1&pagewanted=all

Bercovitch, S. (1978). The American Jeremiad. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison.

Chaplin, J. E. (2003) Expansion and Exceptionalism in Early American History. The Journal of American History, 89(4): 1431-1455.

Clemons, S. (2010). McChrystal’s ”Confidence Job” on Carl Levin and Al Franken. The Huffington Post, online: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/steve-clemons/mcchrystals-confidence-jo_b_425936.html

Cosmides, L. & Tooby, J. (1992). The Psychological Foundations of Culture. In: The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the generation of Culture. Oxford University Press, New York.

Curtis, A. (2004). In: The Power of Nightmares. Documentary series, BBC Two on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eOlwbaPe2os

Davis, D. B. (1986). American Jeremiah. The New York Review of Books, online: http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/1986/feb/13/american-jeremiah/?pagination=false

Duncan, R. & Goddard, J. (2009). Contemporary America. 3rd ed., Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Foner, E. (2001). American Freedom in a Global Age. The American Historical Review, 106(1): 1-16.

Foner, E. (2003). Who owns History? Hill and Wang, New York.

Gelfert, H.-D. (2006). Typisch amerikanisch. Wie die Amerikaner wurden, was sie sind. 3rd ed., C. H. Beck, München.

Heiskanen, B. (2009). A Day Without Immigrants. European Journal of America Studies, Special issue on Immigration, 3: 1-14.

Hersh, S. M. (2003). Selective Intelligence. The New Yorker, online: http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2003/05/12/030512fa_fact

Jefferson, T. (1774/1998). Notes on the State of Virginia: Query XIV. Penguin Classics, London.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA.

(LC-DIG-ppmsca-09855, digital file from original print: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ppmsca.09855)

Lippmann, W. (1922/2008). Public Opinion. BN Publishing.

Loconte, J. (2010). Two Cheers for American Exceptionalism. The American, online: http://www.american.com/archive/2010/march/two-cheers-for-american-exceptionalism

Madsen, D. L. (1998). American Exceptionalism. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh.

Rosenthal, A. (2012). President Obama’s Kill List. The New York Times, The Opinion Pages, online: http://takingnote.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/05/29/president-obamas-kill-list/?ref=world

Soros, G. (2010). The Soros Lectures: At The Central European University. Public Affairs™, New York.

Tucker, R.W. & Hendrickson, D.C. (1992). Empire of Liberty: The Statecraft of Thomas Jefferson. Oxford University Press, New York.

U.S. Government Printing Office: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/search/home.action

U.S. intervention timeline. Global Policy Forum: http://www.globalpolicy.org/component/content/article/155/26024.html

Winthrop, J. (1630). A Model of Christian Charity, online: http://religiousfreedom.lib.virginia.edu/sacred/charity.html

[1] Foner, E. (2001). American Freedom in a Global Age. The American Historical Review, 106(1): 8.

[2] Bercovitch, S. (1978). In: The American Jeremiad. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 81.

[3] Thomas Paine, in: Duncan & Goddard, Contemporary America, 251.

[4] Davis, D. B. (1986). American Jeremiah. The New York Review of Books, online: http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/1986/feb/13/american-jeremiah/?pagination=false

[5] Foner, American freedom in a Global Age, 6.

[6] Hersh, S. M. (2003). Selective Intelligence. The New Yorker. Online: http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2003/05/12/030512fa_fact

[7] Lippmann, W. (1922/2008). Public Opinion. BN Publishing, 74.

[8] Ibid., 190.

[9] Foner, American Freedom in a Global Age, 11.

[10] Ibid., 2.

[11] U.S. intervention timeline, in: Global Policy Forum, http://www.globalpolicy.org/component/content/article/155/26024.html

[12] Duncan & Goddard, Contemporary America, 259.

[13] Ibid., 272-273.

[14] Ibid., 274.

[15] Becker, J. & Shane, S. (2012). Secret ‘Kill List’ Tests Obama’s Principles. The New York Times, online: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/29/world/obamas-leadership-in-war-on-al-qaeda.html?_r=1&pagewanted=all

[16] Rosenthal, A. (2012). President Obama’s Kill List. The New York Times, The Opinion Pages, online: http://takingnote.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/05/29/president-obamas-kill-list/?ref=world

[17] Curtis, A. (2004). In: The Power of Nightmares. Documentary series, BBC Two on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eOlwbaPe2os

[18] Ibid..

[19] Soros, G. (2010). The Soros Lectures: At The Central European University. Public Affairs™, New York, 67.

[20] Clemons, S. (2010). McChrystal’s ”Confidence Job” on Carl Levin and Al Franken. The Huffington Post, online: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/steve-clemons/mcchrystals-confidence-jo_b_425936.html

[21] Akerlof, G. A. & Shiller, R. J. (2009). Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Economy. Princeton University Press, New Jersey.

[22] Loconte, J. (2010) Two Cheers for American Exceptionalism. The American, online: http://www.american.com/archive/2010/march/two-cheers-for-american-exceptionalism