by Majken Hirche

The great heyday of national romantic expression in American arts took place in the later decades of the 19th century as part of an extensive nostalgic celebration of the 1840s and 1850s America.[1] Embedded in this national romantic spirit the German-American painter John Gast was hired to paint a picture for a travel guide. The picture, called American Progress (Ill.1), has become one of the most famous allegories of Manifest Destiny, a concept that was implied in the expansive colonial period, and more evidently expressed in the profound rhetoric of politicians and writers from the 1830s and onward.[2] In all its simplicity, this ‘original myth’ of Manifest Destiny was the belief that America and the American people, led by God, were destined to expand the American territory from the Atlantic Ocean in east to the Pacific Ocean in the West.[3]

Picture: 1. John Gast, American Progress.[4]

Picture: 1. John Gast, American Progress.[4]

The original picture from 1872 was named Westward Ho/Manifest Destiny.[5]

What strikes at first glance is an oversize Columbia[6] dressed in white with a bright star in her hair. She carries a school book in her arm,[7] and hovers the plains of America while unrolling a telegraph wire, and although the picture is painted from bird’s-eye view, Columbia seems to permit the spectator only to look at her from below. The heavy symbolism makes the picture almost didactic in nature: this is the American spirit. Raised above ground to be gazed upon, shining and shedding light on its path, bringing with it the great idea of freedom, liberty and democracy. The school book symbolizes the belief in education and learning as the best path to a successful life,[8] and the telegraph wire points the direction for the hard working and self-reliant American people, and for the technological progress and enlightenment. At Columbia’s feet the movement of things and people go from right to left, or East to West, from a bright and sunlit landscape inhabited by people and machines, to an obscure and almost empty landscape. The settlers, cowboys, wagons and trains move forward, pushing in front of them darkness, hordes of wild animals and marginalized Indians, who look back and up in terror as they almost flee off the canvas.

It is as if the very movement is created by Columbia herself, who, like a broom, seems to sweep off the barbarism and wilderness, all the ignorance and darkness, as if it was dust on a floor that needs to be swept. At the frontier of dust and cleanness dark clouds rise from the process, but they slowly disappear and become ever more white, never leaving behind any residue of dust and grime. It may sound profane to interpret Columbia as a sweeping broom, but that is what Gast’s picture is suggesting in its most basic and iconic form: an entity hovering above earth, progressively wiping the ground in a non-violent way, making all incivility flee and all darkness enlightened. Moreover, she embodies the work ethics of a protestant, relentlessly working and pushing forward, creating plentiful intellectual and material rewards on her way.

Within the picture is also implied the idea of American exceptionalism, a concept frequently used to characterize the American national identity, and its “development from Puritan origin to the present”.[9] In its most simple form, exceptionalism is the belief that you are something special, and probably also a tiny bit better than everybody else. Thus, exceptionalism needs to be contrasted in order to exist, and therefore you like to be exceptional in a group where you can compare. Psychologically speaking, exceptionalism is a dynamical phenomenon, much like group dynamics in school yards, social associations or platoons of soldiers. If you are a member of the group, you enjoy all the benefits, and if not, you don’t. If you aspire towards membership there may be strong barriers, people who oppose you, tease you, bully you and try to throw you out again. Especially the oldest members might find you suspicious or even hate you, while the newest members might help you. Only with time, persistence and a lot of adaptability you will eventually become a full member.

The American variation of exceptionalism contains the model of a society with some very specific values and ideals, first of all the idea of a society build on freedom, liberty and democracy, and the belief that ”all men are created equal […] and with certain unalienable rights”.[10] American exceptionalism also contains the idea that ”America and the Americans are special, exceptional, because they are charged with saving the world from itself and, at the same time, America and Americans must sustain a high level of spiritual, political and moral commitment to this exceptional destiny”.[11] America must be a “city upon a hill”,[12] an exemplary nation to lead and to be watched by the world.

Of course, for an idea like exceptionalism to survive and thrive through hundreds of years in a nation, it needs not only to contain a core idea full of important truths and insights. It also needs to be adaptable and open for new interpretations in order to accommodate for contradictions and changes within. It is therefore the intent in the next few pages of this thesis to track down some important manifestations of American exceptionalism, and look at how American exceptionalism as national identity is interpreted, and more importantly how American exceptionalism may have been reinterpreted and changed in the light of contradictory facts and historical changes.

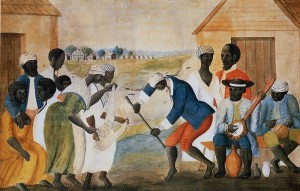

The first and most glaring example that will be looked at is America’s long history of slavery. In the eyes of a 21st century American citizen, slavery might seem like a strange barbaric relic in stark contrast to national ideology and self-understanding, but in the time of Jefferson, slavery was a most natural thing and in no obvious way in opposition to the ideals of the Constitution and American exceptionalism.

Following, this thesis will look at how the later waves of immigrants have been seen as both an opportunity and a problem, and how the continuing debates about who is allowed to be an American have shaped the ideas of citizenship and civil rights.

Finally this thesis will look at how American exceptionalism has transformed itself into a global mission: to spread the great idea of freedom, liberty and democracy to the whole world through military, economic and cultural might, and how America in the process has come to be seen as both an inspiration and a corrupting Superpower.

The Slavery Question

“All men are created equal” says the Declaration of Independence,[13] but dust is dust, and black is black, and it cannot be brushed white. Such was Jefferson’s stance on slavery, and he was not alone in his view. Most Americans at that time believed that non-whites were deficient by nature and therefore not eligible for naturalization as republican citizens.[14] This racist argument is the well known naturalistic fallacy of ‘is equals ought’, with roots deep into historical time, and with continuous reformulations into present day. But Jefferson enumerated even more arguments: “It will probably be asked,” he said in his Notes on the State of Virginia,[15] “why not retain and incorporate the blacks into the state, and thus save the expense of supplying, by importation of white settlers, the vacancies they will leave? Deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites; ten thousand recollections, by the blacks, of the injuries they have sustained; new provocations; the real distinctions which nature has made; and many other circumstances, will divide us into parties, and produce convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race. – To these objections, which are political, may be added others, which are physical and moral.”

“All men are created equal” says the Declaration of Independence,[13] but dust is dust, and black is black, and it cannot be brushed white. Such was Jefferson’s stance on slavery, and he was not alone in his view. Most Americans at that time believed that non-whites were deficient by nature and therefore not eligible for naturalization as republican citizens.[14] This racist argument is the well known naturalistic fallacy of ‘is equals ought’, with roots deep into historical time, and with continuous reformulations into present day. But Jefferson enumerated even more arguments: “It will probably be asked,” he said in his Notes on the State of Virginia,[15] “why not retain and incorporate the blacks into the state, and thus save the expense of supplying, by importation of white settlers, the vacancies they will leave? Deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites; ten thousand recollections, by the blacks, of the injuries they have sustained; new provocations; the real distinctions which nature has made; and many other circumstances, will divide us into parties, and produce convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race. – To these objections, which are political, may be added others, which are physical and moral.”

Apart from the ‘real distinctions nature has made’, Jefferson uses pragmatic objections of prejudice, possible revenge and a bit of aesthetic and ethic handwaving, showing a man who has in mind the practical task of nation building, and not so much the defence of American exceptionalism as it was understood in Jefferson’s time, namely as an “empire of liberty”[16] and a model of democracy from hence some day “it is to be lighted up in other regions of the earth, if other regions of the earth shall ever become susceptible to its benign influence.“[17]

Later during the 19th century, such lazy arguments defending racism were more difficult to hold. But only in relation to black slaves, not the Indians. In contrast to slaves, the exclusion of Indians was a confirmation of the ‘original myth’ because it was the Indian wars which helped to form the myth of the expanding and exceptional ‘American broom’ in the first place: by sweeping away Indians and taking their land, colonists and settlers “developed a national mythology in which ‘American’ technological and logistic superiority in warfare became culturally transmitted as signs of cultural-moral superiority”, says Deborah. L. Madsen.[18] As previously noted, the idea of Manifest Destiny held that the Americans were ‘exceptional’ and blessed by God with a divine mission to claim and inhabit the West. According to Madsen, “European and ‘American’ ‘civilisation’ morally deserved to defeat Indian ‘savagery’ – Might made right and each victory recharged the culture and justified expansion.”[19] Joyce E. Chaplin further explains that in its old form American exceptionalism “stressed the positive achievements of white residents of North America” and “shunned whatever might have been tragic and ambiguous about their handiwork.”[20]

While Indians were the dust and grime at the frontier of civilization, slavery was an impurity from within. And while the inherent contradictions of the existence of slavery grew during the end of the 18th century and the early 19th century, so did the political divide between abolitionists in North, who wanted to set the slaves free, and the American South which depended heavily on imported slave labour from Africa.[21] Abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison used their high moral ground to argue their case, saying that slavery contradicted the principles on which the country was build. As a counter move the Southern states sought legal means to keep slavery working, and to insulate it from outside influence,[22] that is, from Congress and the government. This was not difficult because the Bill of Rights only protected individuals against infringements by the national government but not the states,[23] and several court cases, of which the Dred-Scott decision in 1857 is the most famous,[24] supported their efforts in this regard.

Raising the stakes, Garrison “branded the Constitution as pro-slavery, and called for its abrogation.”[25] Not much happened, though, except a continuous deterioration of the political union and of the discriminatory conditions under which the slaves had to live both in the South and the North. Only in 1860, when Abraham Lincoln became president, things changed. Lincoln was against the spread of slavery into the Western territories. Faced with the threat of anti-slavery laws, the Southern states seceded from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America, which ultimately led to the Civil War.[26]

What Jefferson feared would “divide us into parties” finally had happened, not because slavery had been abolished, but because it had not. After the Civil War the inclusion of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments abolished slavery, enforced the powers of the federal government and created a national citizenship, making it a protected right to vote for black men. “These measures altered the definition of American citizenship, transformed the federal system, and engrafted into the Constitution a principle of racial equality entirely unprecedented in both jurisprudence and political reality before 1860.”[27]

Widening the Circle

The ‘American broom’ had swept clean the land from coast to coast, and had paved the way for millions of immigrants so that they could achieve their dreams of building a new life in a free, democratic and bountiful country. Its defenders had even abolished slavery which had become a most disfiguring stain on the grand display of exceptionalism. But of course, virtue requires vigilance, and what looks good under a reading lamp does not necessarily look as well under street lights.

Although slavery had been removed, its racist roots and practices had not. Slowly slavery transformed into a system of suppressed and cheap labour force that not only consisted of black people but increasingly of Italian, Greek, Polish, Hungarian, Russian and middle eastern immigrants who were mostly unlettered, poor, religiously different and politically unwanted in their home country.[28] These people came mainly between 1890-1924, and were confronted with suspicion, hatred and fear among the “old immigrants”.[29]

One thing to remember about racism is that it is a confused and ad hoc emotion. In fact, modern evolutionary theory suggests that racism itself is not a natural instinct rooted in genetic predispositions as such. Through most of history humans almost never encountered members of other races, which meant that natural selection could not have developed any genetically coded instinct against other races. Instead, the researchers believe that the use of ‘race’ is a proxy indicator of coalition membership, so that one can make a quick and dirty guess about ‘which side’ another person is on. In this sense, racism has the same roots as sexism, chauvinism and other kinds of prejudiced xenophobia.[30]

The United States of America is one of the biggest social experiments in history. An experiment where millions of very different people meet in order to build a common home. It is no surprise then that some of the most persistent and important social indicators of group identification become a powerful political force. Thus, the most important challenges for American exceptionalism during the period after the Civil War – and in fact until this day – are centred on conflicts about who should get citizenship, and who should have the benefit of civil rights, such as equal protection under the law, the right to vote, property rights, non-segregation etc.

Accordingly, policies about who was allowed to be an American were both “inclusive and discriminatory”[31] depending on how much prejudice was in power. Mainly, it has been a positive story: the Chinese Exclusion Act from 1882 prohibited Chinese naturalization.[32] Women got the right to vote in 1920. The National Origin Act of 1924 limited immigration to a quota system based on country of origin, and reduced total immigration from over 800.000 to 164.000 a year.[33] Eisenhower’s ‘Operation Wetback’ dampened immigration from Mexico In 1954.[34] In 1965 the quota system was repealed, and a visa system for family reunification and skills was put in place. In 1971 the Twenty-sixth Amendment gave all citizens above 18 years of age the right to vote. In 1986 the Immigration Act “granted general amnesty and, sometimes, citizenship” to those who could pass a test, and in 1990 Congress raised the total number of legal immigrants to 700.000 a year.[35]

Generally, Heiskanen writes that “a racialized labour force without citizenship rights was allowed into the nation during political stability and economic prosperity; but once a downward tide seemed imminent, legal measures were taken to extradite them.”[36] This shows how a double standard always emerges when exceptionalist ideas clash with economic reality. When push comes to shove, the Broom is a tool for power, not a guard of values.

Movements against immigration have popped up strongly in the last 20 years, especially because of Mexicans and ‘terrorists’, resulting in the Illegal Immigration Act (1996), the USA Patriot Act (2001), the Enhanced Border Security and Visa Entry Form Act (2002) and the Real ID Act (2005).[37] But cheap labour force is also needed, which makes the whole situation even more toxic. Illegal immigrants now have to accept less than minimum pay and all kinds of abuses because they are too afraid to complain. If they did, they just would be sent back. America has two signs at the border: “’help wanted’ and ‘keep out’”, Heiskanen quotes – leading in her eyes to an “unsustainable contradiction between economic and immigration policy.”[38]

Just as it was the case with the deterioration of the condition of slaves in the mid 19th century the principles of reduced production costs trump the rights of immigrants today. The idealistic ‘American broom’ has obviously lost to the ‘Überbroom’ of power und Realpolitik. And even this one believes it has lost because the dust continues to creep into the country from all sides, and that is why it has emigrated in recent decades in order to clean up some other places.

End of part 1.

This essay continues in part 2.

For the list of references, please see part 2.

[1] Aikin, R.C. (2000). Paintings of Manifest Destiny: Mapping the Nation. American Art, 14 (3), 83.

[2] Ibid., 79.

[3] Ibid., 79.

[4] Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-09855 (digital file from original print: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ppmsca.09855).

[5] Gelfert, H.D. (2006). Typisch Amerikanisch. Wie die Amerikaner wurden, was sie sind. 3rd ed., C. H. Beck, München, 14.

[6] Duncan, R. & Goddard, J. (2009). Contemporary America. 3rd ed., Palgrave Macmillan, London, 13.

[7] Gelfert, Typisch Amerikanisch, 14.

[8] Duncan & Goddard, Contemporary America, 7.

[9] Madsen, D.L. (1998). American Exceptionalism. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 2.

[10] From the Declaration of Independence, in: Duncan & Goddard, Contemporary America, 9.

[11] Madsen, American Exceptionalism, 3.

[12] Winthrop, J. (1630). A Model of Christian Charity. http://religiousfreedom.lib.virginia.edu/sacred/charity.html

[13] From The Declaration of Independence, in: Duncan & Goddard, Contemporary America, 9.

[14] Foner, E. (2003). Who is an American? In: Who owns History? Hill and Wang, New York, 154.

[15] Jefferson, T. (1774/1998). Notes on the State of Virginia: Query XIV. Penguin Classics, London, 138.

[16] Tucker, R.W. & Hendrickson, D.C. (1992). Empire of Liberty: The Statecraft of Thomas Jefferson. Oxford University Press, New York, ix.

[17] Ibid, 7.

[18] Madsen, American Exceptionalism, 157.

[19] Madsen, American Exceptionalism,157.

[20] Chaplin, J.E. (2003). Expansion and Exceptionalism in Early American History. The Journal of American History, 89(4): 1432-33.

[21] Duncan & Goddard, Contemporary America, 14-15.

[22] Foner, E. (2003).Blacks and the U.S. Constitution. In: Who owns history? Hill and Wang, New York, 174.

[23] Ibid., 174.

[24] Ibid., 176-177.

[25] Ibid., 174.

[26] Duncan & Goddard, Contemporary America, 14-15.

[27] Foner, Blacks and the U.S. Constitution, 178.

[28] Duncan & Goddard, Contemporary America, 66.

[29] Ibid., 66.

[30] Cosmides, L. & Tooby, J. (1992). The Psychological Foundations of Culture, in: The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the generation of Culture. Oxford University Press, New York, 19-136.

[31] Duncan & Goddard, Contemporary America, 66.

[32] Heiskanen, B. (2009). A Day Without Immigrants. European journal of American studies, Special Issue on Immigration, 3: 3.

[33] Duncan & Goddard, Contemporary America, 68.

[34] Heiskanen, A Day Without Immigrants, 3.

[35] Duncan & Goddard, Contemporary America, 68.

[36] Heiskanen, A Day Without Immigrants, 4.

[37] U.S. Government Printing Office: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/search/home.action

[38] Heiskanen, A Day Without Immigrants, 5.